TGTE - Homeland தாயகம்

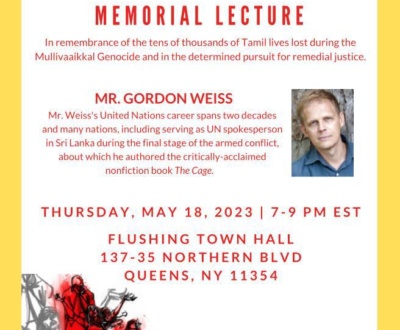

Seventh Annual Mullivaikal Memorial Lecture Delivered by H.E. Mr. Adama Dieng Virtual, 18 May 2021 – TGTE.

- May 21, 2021

- ENGLISH NEWS, TGTE

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

Seventh Annual Mullivaikal Memorial Lecture Virtual, 18 May 2021 – TGTE

Lecture delivered by H.E. Mr. Adama Dieng, Former UNSG Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide

Dear friends,

Brothers and Sisters in Humanity,

At the outset, allow me to express my heartfelt solidarity and closeness to the people of India, Sri Lanka and the South Asia region ravaged by the second wave of Covid-19 infections. My special prayers that the Almighty God grant healing and consolation to everyone affected by this grave pandemic, and in particular to those who are mourning the loss of their loved ones.

Brothers and Sisters,

Today, we gather to mourn the thousands of civilians’ lives lost and we honor those who survived. Remembering these victims, the tens of thousands of civilians who died during the war in Sri Lanka, challenges us all to do more – to fight for the shared justice goals and to prevent past from repeating.

The Mullivaikal Memorial serves as a reminder of victims of war wherever they are. In remembering the people of one community, we remember all communities affected by armed conflict. Memorization of the past is important for the future. Honouring not only the suffering but also the resilience and dignity of victims creates spaces for learning and dialogue about legacies of violence.

This is particularly important for such a long and complex conflict as that of Sri Lanka. Over decades all communities had their share in their suffering, and importantly also their responsibility in atrocities committed by all sides. 12 years after the end of an armed conflict in Sri Lanka, justice remains elusive for Mullivaikal victims and othersurvivors in Sri Lanka. At the same time, victims, and their families despite tremendous burden, involving security risks, social risks, economic costs continue to fight for justice and accountability.

I have been closely engaged with Sri Lanka for over three decades and I personally visited the country in 1998. I remember in early 1980s, the International Commission of Jurists, an organization I had the privilege to lead as Secretary General, commissioned a report on “Ethnic Conflict and Violence in Sri Lanka”. In this Report, we made a careful survey of the background, causes and nature of ethnic violence in this country. We also examined legal and administrative measures adopted by the government to address them. Its little wonder then that, issues and challenges we noted by then are still at the centre of ongoing challenges engulfing the country today. As noted almost forty years ago, inability and unwillingness of the government of the day to pursue credible route to reconciliation among its diverse members of its polity, investigate and punish those who commit serious violations of national and international law and recognize the suffering and humiliation endured by the victims, continue to haunt this country.

Brothers and Sisters,

More than a decade on from the end of the war, the Sri Lankan government has failed to make any credible and meaningful progress towards accountability for international crimes, reparation for victims for harm suffered, or accountability for disappearances and other abuses.

I am pleased and indeed honoured to join members of this audience to share my thoughts on the importance of justice and accountability as the foundation for enduring peace. A topic I care deeply not so much because of my previous roles as an Adviser on prevention of genocide or my work at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), an international Tribunal established to render justice in the post genocide of the Tutsi in Rwanda, but because I wholeheartedly believe that you cannot achieve peace without commitment to justice. Likewise, you cannot achieve justice, without willingness to address impunity. Failure to advance justice and accountability is the precursor to impunity which breeds violence and instability. Unfortunate development, we continue to witness in this country.

Since the end of war more than ten years ago, the United Nations has supported wide range of measures to address the aftermath of the conflict. This is true especially taking into account the fact that, successful fight against impunity and supporting peaceful coexistence and social cohesion will require collective efforts from both international and national institutions and actors.

It was in the aftermath of the conflict, that the Secretary General of the United Nations, established and championed the Human Rights Up Front initiative (HRUF). This initiative was part of the recommendation of the Internal Review Panel on Sri Lanka, which had suggested that the UN review its own action during the end phase of the conflict between the government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). The initiative recognizes the critical role and primary responsibility of Member States to protect their populations from atrocity crimes.

The initiative is therefore meant to concretize what is already reflected in the UN Charter, the UDHR and various UNGA resolutions on the protection of human rights. It reaffirms the centrality of human rights to the objectives of the UN and calls upon the international community to address human rights violations before they escalate and result in the loss of human life. Despite the laudable nature of the initiative, we all agree that the initiative has not been a panacea in this country.

Key UN human rights bodies including the General Assembly and Human Rights Council (HRC) have undertaken wide range of initiatives to push for accountability in Sri Lanka, yet it is true that no measures have yielded outcome that we would all desire to achieve especially on accountability and recognition of the victims in this country. I am pleased that few weeks ago, the HRC in its sitting in Geneva, adopted a resolution mandating the High Commissioner to investigate and preserve evidence for possible accountability in the future. It is my sincere hope that, these efforts will result into a real accountability for those responsible for heinous crimes committed against people of this country.

In absence, of willingness and commitment of the government to pursue accountability, promote reconciliation and recognize the suffering of victims, it is evident that, international route remains a realistic way of achieving justice for the victims. However, recognizing the centrality of the Sri Lankan government and its people in any credible accountability efforts, we continue to encourage the government of Sri Lanka to work with its international partners to achieve accountability and recognition of the suffering of victims. The imperative nature of this cooperation and partnership, emanates from Sri Lanka’s international obligation embedded in wide range of treaties and conventions that the country is bound. In this regard, I cannot but refer to the Geneva Convention drafted in 1949, at a time the idea of protecting civilians in times of war was novel. Today this Convention is universally ratified and there are expectations that it should be fully integrated in law and practice. The universal ratification should bring more compliance, but as the ICRC President has remarked, serious challenges remain:

Quote: “It is true of course that the wars have changed significantly since the Second World War. We are all aware that there have been fewer international armed conflicts while non-international ones have multiplied.

“Today too, conflicts have become more intractable. The Second World War lasted six years – many of the conflicts we see today have lasted for years or decades, affecting generations.

“Battles are fought in populated areas, risking too many civilian lives, and destroying critical infrastructure. In protracted, urban wars we are seeing great numbers of people affected, for long periods and with deep needs: from food, water, and shelter, to health care services and economic opportunities and the need for psycho-social support.” End Quote.

A year before the Geneva conventions were finalized, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the UN General Assembly. The Declaration reminded us that we are all born free and equal in dignity and rights, irrespective of our race, ethnicity, gender, or political views. On 9 December 1948, a day before the adoption of the UDHR, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was also adopted by the UN General Assembly.

Upholding the worth and dignity of all has been the principle underlying the work of the United Nations in peace, development, humanitarian action, and human rights. These are not empty words but are enshrined in legal norms and are embedded in the work of institutions, particularly those that pursue justice and accountability.

Accountability for the most serious violations is a cornerstone of the human rights architecture and an essential demand of victims. As I mentioned earlier, I had the honour to serve on the ICTR. My daily work at the tribunal was a reminder that accountability for war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide is an important part of peace-building, or reconciliation between communities and for forging peace within society. That peace cannot be achieved by ending the conflict – peace without justice is not a real peace – it is a driver for another conflict.

Justice is not retribution. It is not an act of revenge. It is not about putting one community above another. Justice should work for the benefit of all. It should be in the interest of all the society to pursue the truth, know what happened and support victims from all communities and repair the harm they incurred, and embark on institutional reforms to ensure. The combination of these measures can effectively break cycles of impunity and ensure that conflict will not return.

Dealing with the past is dealing with the present. Dealing with the past is the way to a just future. Societies have found transitional justice to be a useful vehicle. Prosecuting individuals for human rights violations that constitute international crimes weed out suspected criminal from society. Learning the truth and giving voice to victims is the first step towards reconciliation. Establishing reparations programmes to help victims and survivors shows that the society upholds the dignity of each of its members, irrespective of their ethnicity. Bringing about institutional reforms guarantee that the violations of the past are not repeated.

Justice process enables us to deal with difficult issues. Take for instance the most milestone judgment of the international criminal court in the Ongwen case. In his conviction and sentence, the ICC has weighed complex moral and legal issues. Abducted at 10 and turned LRA child soldier, now at 41, he rightly has to account for his own atrocities, even if once a victim.

Governments are increasingly diverting attention – both politically and financially – from continuing to support transitional justice processes, stressing that the COVID-crisis requires that the maximum of expenses go into direct measures fighting pandemic. While this reallocation of funding is understandable under the current financial constraints, it risks that important achievements reached by some countries on their transitioning path will be made undone.

Also, the COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying recession have magnified structural gaps and hence their impact across society has become more visible. Connecting and empowering people through justice is a fundamental component of a rule of law-based society. At the heart of the violations are policies and practices that privilege some at the account of others. We saw how such policies unfolded during the COVID-19 pandemic with ethnic minorities in affluent societies bearing the brunt of the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also impacted on religious freedom and exacerbated the prevailing marginalisation and discrimination suffered by the Muslim community. There has been concerns about the Government of Sri Lanka’s decision to mandate cremations for all those affected by COVID-19. This has prevented Muslims from practicing their own burial religious rites, and has disproportionately affected religious minorities and exacerbated distress and tensions. Although the Government asserted to OHCHR that this policy is driven by public health concerns and scientific advice, the High Commissioner for Human Rights noted that WHO guidance stresses that “cremation is a cultural choice”. Sri Lankan Muslims have also been stigmatized in popular discourse as carriers of COVID 19.

We must also recognize that over the last 10 years since the end of the conflict, the Muslim community has been at the receiving end of the growing Sinhala Buddhist nationalism, challenging the identity and existence of the Muslim community. Whether it is the riots of Aluthgama in 2014, the Kandy riots of 2018 or the aftermath of the Easter Sunday attacks, the Muslims have been on the receiving end. Noting what they have been experiencing, including haphazard detentions and harassment, One can say that there is a point of synergy and alignment between the Muslim community and the Tamil community.

The COVID 19 experience has challenged the Muslims to think that they are not able to live or die in Sri Lanka. With the case of the Muslims, it appears to be a clash for very existence. But what this means is that the fate of minorities in Sri Lanka is at a critical juncture. With the rise in extreme Sinhala National Buddhist thinking, no minority (religious or ethnic) is safe and we face something similar to what the Myanmar state is going through. So there has to be a coming together for minorities to really tackle the clear and present danger in Sri Lanka and that is a descent into majoritarian autocracy where no minority is safe. It is urgent that the Government of Sri Lanka engages seriously in managing diversity in the most constructive manner, so that no-one would feel being discriminated. For this to happen there has to be partnership and an outreach. The Tamils also have to reach out to the Muslims and vice versa and trust needs to be built. What happened to the Muslims during the conflict particularly in the 1990s has to be acknowledged. Justice for the Tamils in Sri Lanka means justice for all Sri Lankans. Due to structural inequalities, discrimination and gendered-power dynamics, data has shown that women trust less than men in all types of key institutions (distrust is highest in Government and business sectors).

Against this background, civil society, international organizations and other stakeholders need to keep advocating for continuous political commitments by authorities and that possible avenues are sought after that transitional justice processes can continue to be supported financially.

It is within these parameters that we need to look at the situation of Sri Lanka, 12 years after the conflict between the Government and the LTTE ended. As you may remember, in April 2014, the Human Rights Council requested a “comprehensive investigation” into alleged serious violations and abuses of human rights and related crimes committed over several years. The OHCHR Investigation in Sri Lanka (OISL) report covered alleged serious violations and abuses of human rights and related crimes committed by all sides during the armed conflict between the Sri Lankan Army and the LTTE. The UN action has contributed to the creation of historical record of events, provided a framework for consideration of accountability options and recommended measures to deliver justice and provide reparations to victims.

The Human Rights Council remained engaged in this situation trying to move the communities together towards durable peace. Its resolution 30/1 identified specific measures that would have enhanced justice, truth and reconciliation, and contribute to prevent recurrence. In 2015 we were all hopeful that through embarking in a transformative, reparative, process, Sri Lanka could come to terms with its difficult past, bringing closure to its darkest chapters and looking ahead as a united, inclusive society. The then national unity Government made important commitments to recognize and confront the past abuses, strengthen democratic and independent institutions, end impunity and achieve reconciliation. These commitments were embodied in its co-sponsoring of UN Human Rights Council resolution 30/1.

Between 2015 and 2019 the Government and the UN worked together towards the implementation of an ambitious transitional justice and reconciliation agenda that, if fully implemented, would have gone a long way in resolving the intercommunity tensions, grievances and recurring patterns of violence that have dragged the country for decades.

However, consensus on that promising path towards reconciliation faltered with the dissolution of the Government coalition, lack of political will and most definitely after the change of Government in 2019 and 2020. The Government in 2020 formally renounced the reconciliation agenda when it withdrew its co-sponsorship from the 2015 Human Rights Council resolution that outlined the transitional justice agenda.

A position that not only denies the need for accountability for past crimes but actively obstructs the fight against impunity, will necessarily increase mistrust between communities, crystalize past grievances and generate new ones. In her January 2021 report to the Human Rights Council, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights stated “While the criminal justice system in Sri Lanka has long been the subject of interference, the current Government has proactively obstructed or sought to stop ongoing investigations and criminal trials to prevent accountability for past crimes…… “Given the demonstrated inability and unwillingness of Government to advance accountability at the national level, it is time for international action to ensure justice for international crimes.” The High Commissioner’s report clearly demonstrated that there is no prospect for domestic accountability in Sri Lanka and made a persuasive case for an international action for justice and accountability.

In March 2021 the HRC passed a new Resolution (46/1) that refers to the “accelerating militarisation of civilian government functions”, “the erosion of the independence of the judiciary”, and “increased marginalisation” of Tamil and Muslim minorities. The resolution to which I referred earlier decided to “strengthen the capacity of the Office of the High Commissioner to collect, consolidate, analyse and preserve information and evidence and to develop possible strategies for future accountability processes for gross violations of human rights or serious violations of international humanitarian law in Sri Lanka….”.

The HRC solid engagement prompted some critical reflection and debate, including within the government, about the current direction of the country.

In February this year, I was amongst the signatories of a letter titled “Sowing the seeds of conflict” in which we highlighted the dangerous path Sri Lanka has embarked in the past months and calling on the international community to take immediate steps towards justice and accountability to end Sri Lanka’s cycles of violence. Among the co-signatories of the letter were four previous UN Human Rights Commissioners, a former Deputy Secretary General, a Nobel Peace prize winner and numerous former special rapporteurs and envoys.

We stood together to express concern over the alarms raised in the HC report on Sri Lanka regarding, specifically: the militarization of civilian government functions (including the appointment and promotion of senior military officials identified in earlier UN reports as perpetrators of alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity during the final years of the conflict); the reversal of constitutional safeguards (which undermine, among other things the independence of the judiciary and key oversight commissions on the police and human rights); new sources of political obstruction of accountability for crimes and human rights violations (including by new Commissions of Inquiry that have intervened in ongoing cases); an increase in majoritarian rhetoric and exclusionary policies targeting Tamil and Muslim communities; unceasing surveillance and intimidation of civil society and shrinking democratic space (including the continued use of the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act, despite years of commitment to its repeal and replacement by an Act complying with international standards).

We praised the HC preventive focus because we are all aware that in 2009 the international community failed Sri Lanka. We must not fail again. Since then, much has been learned about prevention. A consensus has emerged on the need to broaden and to upstream prevention work. Agreement has been reached that the brunt of prevention work is borne by national institutions but that this presupposes sincere and effective commitment to addressing the root causes of violations and conflict.

In Sri Lanka, today, unfortunately a sincere commitment to reconciliation on the part of the authorities remains lacking.

Brothers and sisters,

Let me reiterate my belief that it is through our enduring faith in our common humanity that we can realize society premised on equality, justice, and harmonious coexistence. Preventing atrocity crimes and ensuring accountability for such crimes is a shared responsibility. Let us not stand aside when our fellow human beings are insulted, humiliated and dehumanized as lesser humans on account of their identity, ethnicity, religion, political ideology or when we hear calls for violence by those with influence and power to achieve their objectives whether political, economic or social. It is through our steadfast commitment to justice and accountability that we can truly prevent and address impunity that continue to challenge our ability to co-exist as a human family with shared values.

Let’s always remember that our differences are the foundation of our humanity and a bedrock for our peaceful co-existence. Indeed, all faiths acknowledge the inherent strength rooted in this diversity while at the same time recognizing its uniqueness and boundless possibilities it offers. If we cannot recognize and respect our differences and derive inspiration in their potential, we will be failing humanity in all its dimension and manifestations. While everyone has a role to play to foster a culture of tolerance, those in power and in policy making positions have especially a crucial role to play or may I say a sacred duty, to ensure that our differences become a source of unity and strength rather than division and violence. Tolerance cannot be attained when leaders become the source of discord and intolerance. When leaders start labeling names those they disagree with or those who challenge them or those who are simply seeking protection of the law. Such leaders risk alienating and sowing discontent in their communities.

The United Nations Charter, while inspired and emerged from ashes of the tragic events after the second world war, it is also a testimony of our enduring faith in humanity. The Charter was premised on the solemn promise of never again. Yet looking on the current development in the world, we cannot but agree that humanity has failed in its responsibility to uphold the Charter to save humanity from the scourge of war and its consequences. We can pay tribute to the victims of crimes committed in Sri Lanka and elsewhere by honoring the ideals upon which the United Nations Charter was founded. Indeed, we are never short of legal and institutional framework to guide us in this endeavor. What we lack most is human will to make this happen. Our commitment to never again, must start with unflinching commitment to learn from the past, hold to account those responsible for atrocious crimes and gross violations of human rights, and upholding rule of law ideals in all its manifestations.

Before I conclude, I would like to stress five messages:

- Advocacy for accountability must be non-partisan and holistic. It must aim for justice, truth and reparations for crimes and violations committed by all parties. Only such way can defuse grievances and bring genuine reconciliation.

- States have the primary responsibility to bring justice for crimes committed on their territory – but the international community cannot ignore that Sri Lanka today is not ready to provide victims with any form of credible redress. Insofar the culture of denial prevails in Sri Lanka, the international community will have to look at other alternatives: prosecutions under universal jurisdiction, targeted sanctions and any other measure that could dent, if only slightly, the armor of impunity.

- States must do so for the sake of justice, yes, but also for the sake of prevention, because insofar total impunity for gross human rights violations continues to be the norm, the cycle of violence will not stop. New grievances will generate new violence that in turn will be responded with renewed oppression.

- In any accountability process, whether domestic or international the interest of the victims must be at heart, their voices must be heard, their expectations taken into account. Accountability is a worthy cause when it is the right of the victims, and not political agendas, that is at the core.

- Following the Human Rights Council’s clear expressions of concern, I hope the Government will change its course and demonstrate its commitment to justice, accountability, longer-term reconciliation, and protection of minorities. Without acknowledgement of the violations and without dealing with the past violations, there can be no sustainable peace and development in Sri Lanka.

Brothers and sisters,

In conclusion, thank you again for giving me the honour of addressing such an important gathering. I firmly believe that documentation and memorialisation, such as Mullivaikal is an integral part of the human rights response to mass atrocities. They are important to achieve the goals of reconciliation, to develop a shared history of collective memory and especially, to transform relationships between communities. While memory processes do not replace mechanisms for truth, justice, reparation, “without memory, the rights to truth, justice and full reparation cannot be fully realized and there can be no guarantees of non-recurrence.”

Like all societies, Sri Lanka has to confront its past in order to move forward. It needs to put victims and their dignity first and recognize the injustices and sufferings of victims, their families, and communities. Denial of the past is an easy option, but it damages the basic values on which society can be built and thrive. In remembering the victims of the Mullivaikal, we also remember the victims from all sides of the conflict.

I thank you